(This post is too long for email. Click on the title to read it online!)

Since Amy and I have undertaken this two-month hike around Greece, my friend Ben asked me if I could write something about the travels of Paul. Since this blog is “Peripatos: Walking & Talking”, the peripatetic Paul might as well be our patron saint. Our own travels only barely intersected his, and I am no biblical scholar, but Amy and I had a few thoughts on Paul as we walked and talked.

Lindos, Rhodes

Lindos: Bay by Bay

Around AD 51, on Paul’s third missionary journey, Paul stopped briefly in Rhodes.

Ὡς δὲ ἐγένετο ἀναχθῆναι ἡμᾶς ἀποσπασθέντας ἀπʼ αὐτῶν, εὐθυδρομήσαντες ἤλθομεν εἰς τὴν Κῶ, τῇ δὲ ἑξῆς εἰς τὴν Ῥόδον, κἀκεῖθεν εἰς Πάταρα. καὶ εὑρόντες πλοῖον διαπερῶν εἰς Φοινίκην ἐπιβάντες ἀνήχθημεν.

When we had parted from them [the Ephesian elders at Miletus] and had set sail, we ran a straight course to Cos and the next day to Rhodes and from there to Patara; and having found a ship crossing over to Phoenicia, we went aboard and set sail. — Acts 21.1-21.2)

We went to Rhodes! While we spent most of our time in the tiny village of Embonas, we ended our time on the island with a couple of days in Lindos and a couple in Rhodes City. Either one of these places might have been where Paul’s ship put in.

Bay 1: Rhodes

Rhodes (city), is the eponymous capital city of Rhodes (island). It is on the north point of the island, has a spacious harbor facing the city of Patara in Lycia, Paul’s next stop on his trip. What you see today if you walk around the Old City is mostly Byzantine and Ottoman stuff… it is hard to see what it might have been like when Paul went there. The one thing we share with Paul is that we all missed seeing the Colossus standing astride the harbor, although Paul might have seen some of the remnants that survived the earthquake of 226 BC. The harbors of Rhodes are very busy.

The City of Rhodes, on Rhodes, the harbor seen from the Old Town

Bay 2: Lindos

Paul’s ship might have stopped in Lindos, on the eastern side of the island. Lindos is now a huge tourist attraction of the worst sort, quite frankly—lots of aggressively advertised nightclubs aimed at teenagers dragged by their parents on a cultural tour of Greece. By night, Lindos vibrates with That Thumpin’ Bass™ and glows with neon. But there is a cool fortress overlooking the town, and several lovely bays on either side of the town. One of them is “Saint Paul’s Bay”, a small, well-protected anchorage that the locals claim was where Paul stopped.

Saint Paul’s Bay at Lindos, Rhodes

Bay 3: Anthony Quinn

The people of Rhodes are happy to give advice to travellers, and while a few folks recommended Saint Paul’s Bay, everyone recommended a bay named for the de facto patron saint of Rhodes: Anthony Quinn. Quinn was born Manuel Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca in Chihuahua, Mexico; his mother was Mexican and his father was Irish, an immigrant from County Cork. He was in about a million movies in the mid-20th Century, often cast as a character from the Mediterranean (Ulysses), Central Asia (Attila), or the Middle-East (the Bedouin Omar Mukhtar).

In 1961 he was in The Guns of Navarone, with Gregory Peck and Irene Papas. The story is a WWII adventure set on a fictional Greek island but filmed on Rhodes. The production was the best thing that ever happened to Rhodes, to hear the locals talk about it. It put Rhodes on the map, and brought a lot of money into the local economy. And while Irene Papas was the only Greek actor in the movie, Quinn (who plays a Cretan resistance fighter) basically became an honorary Greek. He locked down that status by playing another Greek guy in Zorba the Greek three years later.

One of the scenes in The Guns of Navarone was filmed in a little bay north of Lindos. Quinn wanted to buy it and make it into a resort, and although bureaucracy thwarted his benevolent plan, the place is still called “Quinn’s Bay” after this latter-day saint of the island of Rhodes. We didn’t go there; the picture below is from the Internet.

Anthony Quinn’s Bay

Thessaloniki & Berea

We started our journey in Thessaloniki, and I’ve written about that elsewhere. Paul and his buddy Silas came to Thessalonica (as it was then called) around AD 49, on his second missionary trip; they stayed at the house of a certain Jason. There was a synagogue there, but Paul’s teachings were not well received. The Book of Acts says that a crowd of “some wicked men” (ἄνδρας τινὰς πονηροὺς) formed a mob and were searching for Paul in order to “bring him out to the Assembly” on the crime of “turning the world upside down” and also proclaiming a King other than the Roman Emperor (we’ve heard that before!) [Acts 17:1–17.9].

The harbor at Thessaloniki

Paul and Silas had to flee Thessalonica. This episode was bad P.R. for the city, and there are (as far as I can find) no cities in the United States named Thessalonica, Salonica, or any other version of the name.

The missionaries did find refuge in Beroea (Βέροια), which is now Veria or Veroia, about 30 miles to the west of Thessaloniki. Amy and I did not stop in Veroia on our travels, but we did drive through it on the A2 highway (or, rather, αυτοκινητόδρομοι (aftokinitodromi, “car-racetrack”).

I did however live for a year in “Berea”, a small town, mostly former mill-villages, now incorporated into Greenville, South Carolina. The Greek Beroea extended hospitality to Paul and Silas, and the Carolina Berea did likewise for me and Amy before we bought our first house. Our Berea is a modest place, but has a history of its own.

A historic schoolhouse in Berea, South Carolina, saved from demolition and up for sale.

The Areopagus, or, Mars’ Hill

Paul travelled south, presumably past Thermopylae and Thebes, to Athens. There he gave a public sermon on the Areopagus, the Ἄρειος Πάγος (Areios Pagos), the “Hill of Ares”.

Acts 17.22 σταθεὶς δὲ Παῦλος ἐν μέσῳ τοῦ Ἀρείου Πάγου ἔφη Ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, κατὰ πάντα ὡς δεισιδαιμονεστέρους ὑμᾶς θεωρῶ· 23 διερχόμενος γὰρ καὶ ἀναθεωρῶν τὰ σεβάσματα ὑμῶν εὗρον καὶ βωμὸν ἐν ᾧ ἐπεγέγραπτο ΑΓΝΩΣΤΩ ΘΕΩ. ὃ οὖν ἀγνοοῦντες εὐσεβεῖτε, τοῦτο ἐγὼ καταγγέλλω ὑμῖν. … 32 ἀκούσαντες δὲ ἀνάστασιν νεκρῶν οἱ μὲν ἐχλεύαζον οἱ δὲ εἶπαν Ἀκουσόμεθά σου περὶ τούτου καὶ πάλιν. 33 οὕτως ὁ Παῦλος ἐξῆλθεν ἐκ μέσου αὐτῶν· 33 τινὲς δὲ ἄνδρες κολληθέντες αὐτῷ ἐπίστευσαν, ἐν οἷς καὶ Διονύσιος [ὁ] Ἀρεοπαγίτης καὶ γυνὴ ὀνόματι Δάμαρις καὶ ἕτεροι σὺν αὐτοῖς.

Acts 17.22 Then Paul stood in front of the Areopagus and said, “Athenians, I see how extremely religious you are in every way. 23 For as I went through the city and looked carefully at the objects of your worship, I found among them an altar with the inscription, ‘To an unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. … 32 When they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some scoffed; but others said, “We will hear you again about this.” 33 At that point Paul left them. 34 But some of them joined him and became believers, including Dionysius the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris, and others with them.

The Areopagus, as seen from the Athenian Acropolis

The Areopagus had a long and storied history, too long to recount here. Suffice it to say that over centuries the Areopagus was a setting for important speeches leading to important actions. Aeschylus wrote a play about it, and Aristotle describes it role in Athenian history.

For Paul (a) to have attracted an audience of Athenians onto the Areopagus at all, and (b) to have persuaded some Athenians to say “Ἀκουσόμεθά σου περὶ τούτου καὶ πάλιν” (“We will listen to you on this topic again!”) was a big deal. In Thessaloniki, Paul seems to have talked to the Jewish community. In Athens, he was talking to gentiles in the sophisticated cultural center of the Roman world. For Paul, it must have been like appearing at the Apollo Theater or Shea Stadium.

And in more recent times, the nation of Greece celebrates the Areopagus as much for Paul’s brief visit there as for its foundation by the goddess Athena and its role in the Persian Wars.

An Areopagus Commemorative Postage Stamp

As with Berea, Americans have celebrated the Areopagus and its role in Paul’s mission by naming things after it. Areios Pagos is “Hill of Ares”, or Romanized/Latinized to “Mars Hill”. There is a range of mountains in Antarctica named “Mars Hills”. There are places called “Mars Hill” in Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Maine (two of them!), Indiana, Arizona, and North Carolina.

Here’s a picture from sometime in the 1930s of Hoyt and Olive Blackwell, my grandparents, sitting on the Areopagus, with the Acropolis behind them.

Hoyt & Olive Blackwell on the Areopagus

Hoyt Blackwell (1890–1989) was a veteran of the Great War, a Professor of New Testament Greek, and later President of Mars Hill College from 1938 to 1966.

Mars Hill College

So that’s my personal connection to the Areopagus.

Deisidaimoneō, “…rare in a good sense…”

δεισιδαιμονέω (deisidaimoneō), have superstitious fears, Plb. 9.19.1, D.S. 12.59, Polystr. 9, etc.: rare in good sense, to be religious, Zaleuc. ap. Stob. 4.2.19. Link to LSJ entry

At Acts 17.16, we read that when Paul first came to Athens, he was upset to see that the city was κατείδωλος (kateidōlos), “full of idols”.

If Paul came into Athens from the north—and I’m just guessing and making stuff up here—he would have had to take one of two roads to get around Mt. Parnes, which is directly north of the city. He could have come around the eastern slopes of Parnes, through Decelaia and the gap between Parnes and Mt. Pentelikon (source of Pentelic Marble). But on the assumption that Paul, Silas, and their escorting friends, came through Thebes, the quicker way to Athens would have been through the gap between Mt. Citharon (on the west) and Parnes (on the east). This road led from Thebes to Plataea, and thence to Attica, through Eleutherae and the deme of Oenoe. The Wikipedia article on Oenoe is really good at explaining why Paul might have come this way.

The Sacred Way into Athens

This road was part of the Sacred Way, the road between Athens and Delphi. As it entered the city, it was lined with shrines, altars, and statues in honor of various gods and heroes, from the biggies like Zeus, Athena, and Heracles, to imports like Thracian Bendis. I’m guessing that this display of syncretic polytheism was what incensed Paul.

But he began his speech to the Athenians (Acts 17.22) by being a little sly and witty: Ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, κατὰ πάντα ὡς δεισιδαιμονεστέρους ὑμᾶς θεωρῶ (“Athenian men, I see you all to be, in all respects, rather deeply god-fearing). The operative word is an adjective, a form of δεισιδαίμων (deisidaimōn). It is a compound built from δείδω (deidō), “I fear”, and δαίμων (daimōn), “god, divine power”. So, “god-fearing”. It is in the comparative form, so, “more god fearing” or “rather god-fearing”.

The pre-Christian (“pagan”, whatever you want to call them) Greeks loved to worship their daimones. Socrates had a close personal relationship with his own little daimōn. So for most Athenians, being told that you are “rather daimōn-fearing” was probably not an insult. But I seriously doubt that Paul considered the God of Abraham, YHWH, to be just another daimōn (the Greek word does give us English “demon”, after all). So maybe he was being sly and a little jokey, digging at their pagan beliefs without actively offending his audience. Well, it worked. Sort of.

Paul won over two converts, Dionysius the Areopagite (Διονύσιος ὁ Ἀρεοπαγίτης) and a woman named Damaris (γυνὴ ὀνόματι Δάμαρις) (Luke 17.34).

A few of observations… It is funny that a man named after the drunken-sexy god Dionysus was the first of Paul’s Athenian converts; he was an official of the court of the Areopagus, too (“Areopagite” is a title). There is a mosaic depicting him in the Hosios Loukas Monastery, in Boeotia; that the monastery is dedicated to “St. Luke” is appropriate, if Luke was indeed the author of Acts.

A Mosaic of Dionysius the Areopagite

And, it is nice that Acts actually gives the woman Damaris a name; Acts of the Apostles is good about inclusion in that way. We know literally nothing about her otherwise, although Raphael paints her, so might as well imagine her looking like that.

Raphael’s “St. Paul Preaching at Athens, c. 1515

Her name might come from the Greek word δάμᾰρ (damar), “wife”. Maybe she was simply the wife of Dionysius? Evidently an early translation of Acts into Georgian says so explicitly.

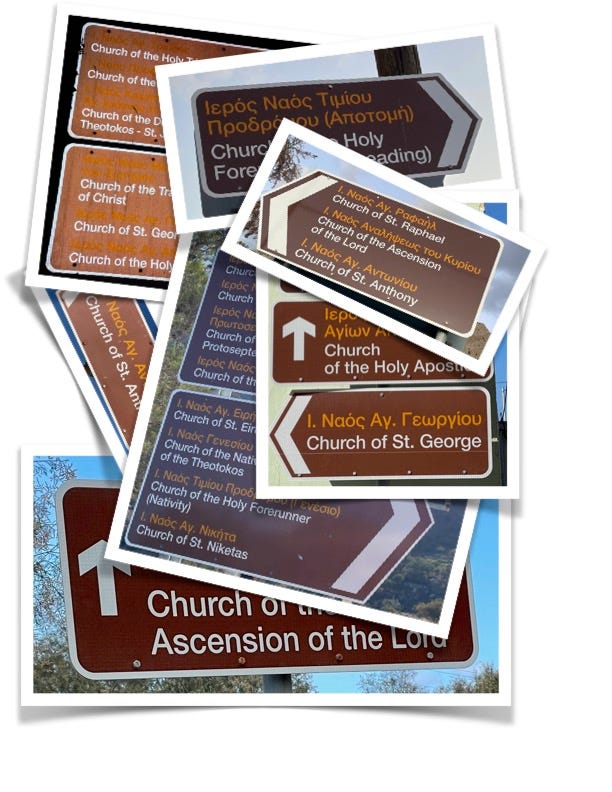

Deisidaimonia in Kavousi

Paul “Sort of” won over the Greeks. Why? I’ll split the answer off into another post, since this has gotten long. But here’s the teaser: In the town of Kavousi, Crete, with a population of 539 souls, there are no fewer than 14 churches, each dedicated to a saint, a particular aspect of a saint, a divine being, a theological concept, or a theologically significant event. So while Christianity very much took over Greek culture in the centuries following Paul, it is possible that the Greeks simply brought their deisidaimonia along with them.

The Churches of Kavousi

Peripatos: Walking & Talking with Amy and Christopher Blackwell © 2024 by Amy G. Hackney Blackwell & Christopher W. Blackwell is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0